Background:

As part of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and PBS’s Ready To Learn initiative, The Adventures of The Electric Company on Prankster Planet was created in 2010 when the U.S. Department of Education was looking for transmedia (i.e., multiplatform) storytelling ideas to improve young children’s math and literacy skills. In this “Prankster Planet” series, animated characters from the PBS Kids show The Electric Company were pitted against the Pranksters on a planet in space. The characters’ interactions cycled through a combination of storylines on television and online games that kids could play as a way to continue the story. These web-based games were “missions” that centered on math and literacy concepts from the television show.

Scrapyard Slice was one of these games, and focused specifically on distinguishing parts of compound words. This skill is an important component of literacy development. In the mini-game, words swing across the screen on beams, and players have to break apart the compound words to prevent the bots from dumping them into the junkyard.

Research questions

- Can children in first and second grades identify compound words?

- Can kids figure out how to play the game?

- Do kids stay engaged throughout the entire game?

Process

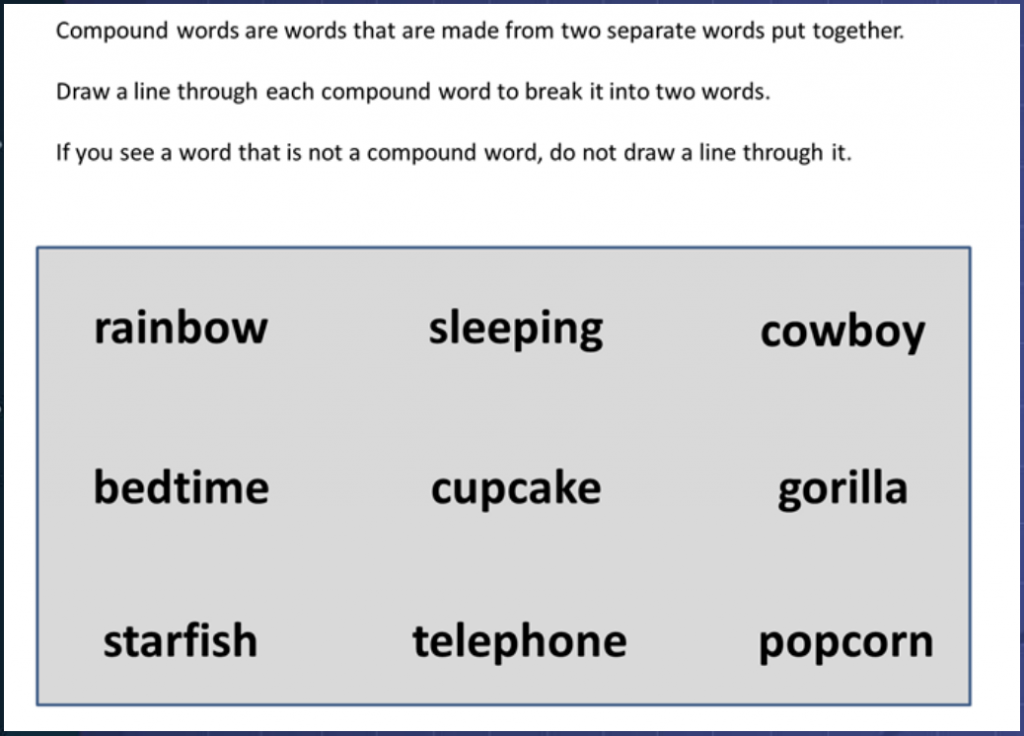

At the earliest stage of playtesting, researchers worked one-on-one with nine first and second graders at Sesame Workshop. The researchers administered a worksheet and read aloud the directions to the kids.

Later on, to test the usability and enjoyment of Scrapyard Slice, researchers worked one-on-one with 17 first and second graders at a charter school in New York City and 15 first, second, and third graders at an independent school in New York City. The kids played through the mini-game on a laptop or touchscreen device for five minutes.

Separate content

To test whether kids in the target age group would understand the core concept behind the game, researchers asked kids to draw a line through the compound words on a simple worksheet. By separating the content from the product, the researchers were able to eliminate any distraction or confusion caused by the game, allowing them to focus more specifically on the learning content.

Rough is right

When testing the alpha prototype, it was clear to kids that the game was not finished. Prior to playing, kids watched a separate video that gave instructions on how to play the game. Because voice-over was not yet recorded, the researcher read scripted prompts and feedback lines as needed. This allowed the researchers to gain insights on their questions without having to wait for every detail of the game to be finished. Plus, despite the instructions and audio not being polished in the game itself, they were still able to test how well kids understood them.

Pain points

As the kids played through the game, the researchers observed the actions they took: Were there interruptions to kids carrying out actions and why? Why were kids ever not able to slice words? Were there accidental inputs or actions and why?

Notice the nonverbal

Researchers paid close attention to kids’ expressions and behavior to see when the game held their interest and when they became frustrated or impatient.

Findings

- When researchers watched kids play the game, they saw that some kids sliced every word on the screen, instead of just targeting the compound words. Since they had already determined that kids were able to identify compound words on a piece of paper, they concluded that this confusion in the game was due to limited instructions and unclear feedback.

- Researchers noticed two specific pain points that prevented kids from playing the game as intended. When attempting to slice words at the top of the screen, kids accidentally pulled down the device’s menu. And when multiple words overlapped on screen, kids weren’t able to slice the word they wanted.

- By paying close attention to kids’ expressions and behavior, researchers noticed that kids became impatient when there were long stretches of time in which only non-compound words appeared on the screen. Yet, even with shorter gaps between compound words, researchers noticed that about a quarter of the kids who tested the game lost interest during the five minute game.

Impact

- In the final version of the game, the instructions were updated to better define the concept of a compound word, and to clarify that some non-compound words would also appear.

- Designers also added cues throughout the game to provide feedback: If a child incorrectly slices a non-compound word, a “-1” shows up the first time. If they repeatedly try to slice non-compound words, then the compound words start to glow green.

- Game designers lowered the words on the screen and made them overlap less, so they would be easier for kids to slice.

- The length of time between compound words appearing on screen was also shortened.

- The game was ultimately shortened to three minutes in order to keep kids engaged throughout.

Play Scrapyard Slice here!

Wong, C. B. (2013). The Electric Company Ready to Learn: 3 game tests [Unpublished internal document]. Sesame Workshop.