Background

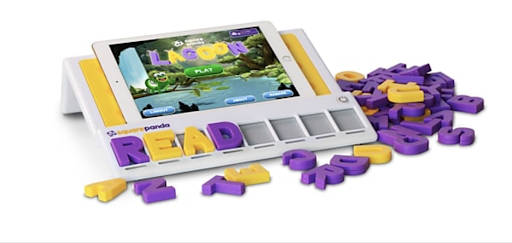

Square Panda makes interactive, multistory games that teach foundational reading skills, for use in the classroom and/or at home. Historically, Square Panda apps were single-purpose, had to be downloaded separately, and could be played in any order. This lack of structure could be overwhelming and confusing, particularly for adults trying to guide their kids. In response, the team wanted to create a comprehensive single app that would contain all mini-games within it; with some intelligence built in, the app could guide children on the next most appropriate game.

As a starting point, the team created a bare-bones prototype that included a “home world” and three mini-games, intended to be played in succession. The overarching goal of initial UX testing was to learn “what we don’t know” about how kids might respond to this more structured approach. This first set of mini-games focused on letter-sound correspondence, so most testers were pre-school age.

Each mini-game was played on a tablet that connected via Bluetooth to a physical tray for holding physical “smart” letters. When a child placed a letter in the tray, the game app would know about it and could provide encouragement or additional guidance as appropriate.

Research Questions

- Can kids successfully navigate the new home world?

- How do kids react to moving through the succession of mini-games?

- What can we observe about curriculum efficacy?

Process

Researchers conducted 1:1, in-person play tests with 10 kids aged 2.5 – 4 years old.

Separate Content

This research project fell under the umbrella of a larger research initiative aimed at tracking efficacy data: how well do kids learn from these games? Obviously a play test is not a substitute for more rigorous, academic-style testing, but it can provide clues for creating hypotheses. As such, the Researcher conducted a before and after assessment test, by holding up a letter and asking the child to name it and then say its sound. The specific letters chosen (S,M,A,P) matched the letters used during the play test. In this way, Researchers were able to roughly gauge how well each child had absorbed the curriculum learned during the play session.

Notice the Nonverbal

Researchers paid particular attention to nonverbal cues of engagement, boredom, and persistent frustration, using the baseline of expressions and behaviors noted during Likes & Dislikes (see above). In particular, they would note sudden changes in behavior, such as long pauses, distractions, or looking towards a parent. When an unusual behavior was noted, it was very important to note exactly what the child was doing just before. Here’s an example of observational notes:

Task: Complete Mini-game A

Observations: Stared at screen for 5 seconds after intro animation

…

In the Noticing phase, the Researcher simply noted each behavior, without assigning meaning yet. It was critical to remain open-minded during this observation step to reduce researcher bias: one child’s pause might be due to an intense focus on curriculum whereas another child’s pause might reflect confusion over what to do next. To help interpret the behaviors, Researchers used Why Variations.

Why Variations

Researchers used a series of follow-up probes to understand the reasons behind the nonverbal behaviors that they observed. For example, after noticing a child pausing, a Researcher might say, “I noticed you paused. What were you just noticing on the screen?…Oh, you were waiting for the character to say something? What do you think they would say?…Oh, you thought they would tell you what to do next, yeah, that makes sense.” (In this particular case, Researchers also slipped in verbiage testing: “Let’s pretend the character said, ‘Tap the arrow to turn the page.’…”)

Findings

Can kids successfully navigate the new home world?

The basic navigation was not intuitive enough initially. The first prototype followed a common gaming convention of expecting the player to tap a destination on screen for their avatar, whereas this very young age group expected to drag their avatar around the screen. During the home world onboarding, virtually all kids would tap and drag their avatar repeatedly. Even after supplying explicit instructions to “tap where you want to go”, kids would often forget and still try to drag the avatar.

How do kids react to moving through the succession of mini-games?

All kids loved getting to explore every available game before repeating a game. After each game, the researcher would ask, “Which do you want to do next: this game again or a new game?” Virtually every child wanted to try each new game, even when they showed strong enthusiasm for the game they had just played. Once they had completed one round of each game, all kids wanted to continue playing, further supporting a hypothesis that curiosity, rather than boredom, was the reason kids wanted to play each new game.

What can we observe about curriculum efficacy?

The team learned a lot about each mini-game as well. For example, one of the games prompted the child to place a specific letter in the tray. Upon placing the correct letter, e.g., “S”, a group of bubbles containing an “S” would appear on screen, ready to be popped (tapped) by the player. Each pop/tap would trigger hearing the sound of the letter S.. However, the initial game design also included distractor bubbles containing a letter other than “S”. Even though the instructions explicitly stated to only pop “S” bubbles, most kids ignored this instruction and rapidly popped all bubbles on screen.

While kids had fun popping bubbles, the curricular lesson was undermined by hearing multiple, interlaced letter sounds layered with both celebrations and wrong-answer feedback. Not surprisingly, these kids did not do well on the post-assessment test.

Impact

Overall, the direction of creating a single app containing multiple mini-games, rather than having a separate app for each mini-game, was validated via UX play tests (as well as market testing); and this initial research gave the team strong design feedback for moving forward. For example, the team added visual support for navigation basics; created a cohesive visual theme to tie the home world to the mini-games; and each mini-game was revamped with feedback from play tests. In the “Bubbles” example above, the game team removed the distractor bubbles and pivoted the game’s curriculum purpose to letter-sound exposure/reinforcement. In conjunction, they created a separate game for letter-sound assessment that used a better fitting game mechanic.

All of these mini-games live in a single app with an adaptive learning architecture. This app is in its second major iteration with 10 times the volume of content from the first version and is played by children in schools and homes across the US and India.

Learn more about Square Panda here!